China and Russia Have a Central Asia Problem

China and Russia Have a Central Asia Problem

China and Russia Have a Central Asia Problem

During Kazakhstan’s recent unrest, Moscow and Beijing seemed to slip into their conventional roles in the region — the “gun” and the “wallet.” But that equilibrium won’t hold.

Russia’s decision last week to help the Kazakh government crush an uprising and China’s muted response have been taken as more evidence of a kind of geopolitical equilibrium in one of the regions most vital to both. Moscow remains the primary security guarantor, the argument goes, while Beijing is content to exercise its influence through investment.

Not quite. Indeed, the aftermath of unrest in Kazakhstan could even surface buried tensions between the two giant frenemies over what happens in their shared backyard, against a changing backdrop that already threatens the idea of an informal condominium of interests.

The unprecedented move by the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization to send troops in response to President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s appeal — something it did not do for Armenia during the Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, for example — certainly reinforces Russia’s role as regional protector, or at least, protector of friendly autocratic regimes. China, meanwhile, did keep a low profile. It was initially silent, then declared the demonstrations were an “internal affair.” Only later did it echo the questionable official narrative, declaring its opposition to “color revolutions” and its willingness to support the fight against the “three evil forces,” a phrase intended to describe extremism, secessionism and terrorism.

- Neo-Nazi Russian nationalist exposes how Russia’s leaders sent them to Ukraine to kill Ukrainians

- Moscow’s Continuing Ukrainian Buildup

- Statements by Ukraine Foreign Ministry at the Meeting with NATO Secretary General

The division of labor narrative is useful. It’s allowed Beijing to pursue its interests behind a stance of non-interference. Russia, meanwhile, has been able to explain away the growing presence of a rival power on its southern border. The Eurasian Economic Union, Russia’s effort at integration, works alongside Beijing’s more expansive Belt-and-Road initiative. Although Central Asia matters to Moscow, no countries as integral to President Vladimir Putin’s sense of national identity as Ukraine or Belarus are involved.

But the distinction is far less neat than the “gun and wallet” aphorism or the past few days suggest, and the balance far less secure.

Take the “wallet.” While trade with China and Chinese investment into energy, mining and infrastructure over the past decade or so have grown at an impressive pace, Moscow’s economic ties to the region are strong. Russian firms still account for a chunk of foreign-owned business, and Russia is still a magnet for the region’s workers. Remittances account for close to a third and more than a quarter of gross domestic product for Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, respectively.

More crucially for the future of this balance, though, there’s the “gun.” China has without question used pipelines and hydrocarbon rents as the primary glue for its relationships in the region. Yet China also has significant military aspirations and security fears, especially in a neighborhood that is seen a necessary buffer between Afghanistan and China’s western territories, home to non-Han minorities who have felt the full force of China’s repressive machinery.

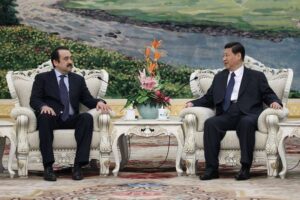

Under an emboldened President Xi Jinping, China has loosened its interpretation of non-interference and moved past Deng Xiaoping’s recommendation that China should hide its strength, bide its time and “never claim leadership.” China has demanded a greater role on the geopolitical stage and expanded its security footprint abroad, including in Central Asia. That’s through private security actors protecting Chinese assets — economic interests are rarely isolated — but also military aid, exercises and, in Tajikistan, troops monitoring a choke point just beyond China’s frontier. Last year, Tajikistan accepted a Chinese proposal to finance a police base on the Tajik-Afghan border.

China has increased its regional security cooperation with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which includes Russia, but also, since 2016, with the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism, a counterterrorism forum that counts Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan. Beijing’s concerns have only increased since the U.S. departure from Afghanistan. None of that will comfort Russia.

Moreover, Kazakhstan’s troubles may prompt Beijing to reassess its vulnerability, given the importance of this vast neighbor which is also an important supplier of uranium, oil, gas and copper — it’s no accident that China chose Kazakhstan to launch its flagship Belt and Road in 2013.

As Temur Umarov at Carnegie Moscow Center pointed out to me, China has limited ability to interfere in Kazakh domestic politics. In that domain, for all the ties between China and the elites (with whom it remains more popular than with a more distrusting general population), Moscow has the upper hand. Putin still has more in common with local bigwigs than Xi does, giving him the confidence to step in and pick sides. China could only wait and see.

But it’s less clear what could happen if China’s interests and substantial investments were threatened. Tokayev, who was handpicked by Kazakhstan’s long-time leader Nursultan Nazarbayev, is now changing the elite guard after ousting his former protector. And as Alexander Cooley, a Barnard College political scientist and Central Asia-watcher, told me, the detention last week of Karim Massimov on state treason charges will have rattled Beijing. A former prime minister who was until recently head of the National Security Committee, Massimov is a Nazarbayev loyalist, but he is of Uyghur heritage, speaks Mandarin Chinese and was seen as the uppermost representative of the China lobby.

None of this suggests conflict in the region or even the Great Game scramble some analysts describe. China and Russia are still autocratic regimes with similar interests, not least in preserving stability, and the timely exit of Russian-led troops from Kazakhstan will reassure. Countries like Kazakhstan will continue to aim for a diplomatic balance. But Russia’s economic capacity to prop up regimes is not increasing. And with changes in the wind, China may no longer wish to remain sitting on the political and security sidelines.

China and Russia Have a Central Asia Problem

By Clara Ferreira Marques